What is a Signal?

First things first: a ‘signal’ is a voltage that varies with time, and it is the output from your guitar - this is important to understand. This signal carries the information about what you’re playing and how you’re playing it like the notes that you play and how hard you play them. The signal is manipulated by the circuitry inside the guitar, then by the circuitry of the effects pedal(s), and then again by the amplifier. Finally, it is output as a sound wave by the loudspeaker.

At a high level overview, everything from plucking an electric guitar string, to some (hopefully expected) sound coming out of the loudspeaker

is relatively simple. The full technical description is included below for completeness, but it is absolutely not necessary to understand this.

Simply put, when you pluck a string, it vibrates. This vibration is felt magnetically by the pickups, and an alternating voltage is induced thanks to

Faraday's law of induction This is then your 'signal' which can be sent to your pedals and/or amplifier.

If that hasn't satisfied you, read on!

How We Hear Our Guitars

When you ‘pluck’ a guitar string, you induce a 'back and forth' vibration on the string. As the string is vibrating, it pushes nearby air molecules back and forth. As the string moves in one direction, the air molecules in that direction are forced to 'bunch up' when the string pushes into them, and this creates a region of high air pressure. When the string retreats, it allows the air molecules to 'relax' and spread out, creating a region of low air pressure. This continues as long as the string vibrates, and so it creates regions of higher and lower pressure which advance through the air at the speed of sound. This continuous oscillation in air pressure is what's called a transverse pressure wave through the air. The animation below should be a very handy visual for this process. The air pressure can then push and pull our eardrums, so we hear the guitar string, even when it's unplugged.

If you pluck the string harder, the vibrations will be stronger, and so the air molecules will be forced to bunch up more at the 'peaks' resulting in a greater peak to peak air pressure (see the y-axis of the bottom plot in the animation below). More pressure means more 'pushing force' on our eardrums, and so we hear a louder sound.

Using the animation below, lets call the position of the string when it is furthest to right hand side 'point x'. As the string approaches point x, a high pressure region forms and will begin moving through the air. The string then moves back to the left, and then toward point x again, creating another high pressure region which begins following the first one at the same speed (the speed of sound). A string that is vibrating more quickly leaves less time between these consecutive visits of point x, and since all pressure waves propagate through air at the speed of sound, regardless of which note was played or its intensity, the distance between each high pressure region is then shorter.

In other words, a faster moving string creates a wave with a shorter 'wavelength', meaning that the regions of 'bunched up' air molecules

(regions of higher pressure) have less distance between eachother. When we talk about the 'frequency' of a note, we're actually talking about how

'frequently' the pressure varies in space. If you pluck your high E string, it will vibrate faster than your low E string, and so the

'frequency' of the pressure wave increases, and we interpret this as a higher pitched (higher frequency) note.

How Our Guitars 'Hear Themselves'

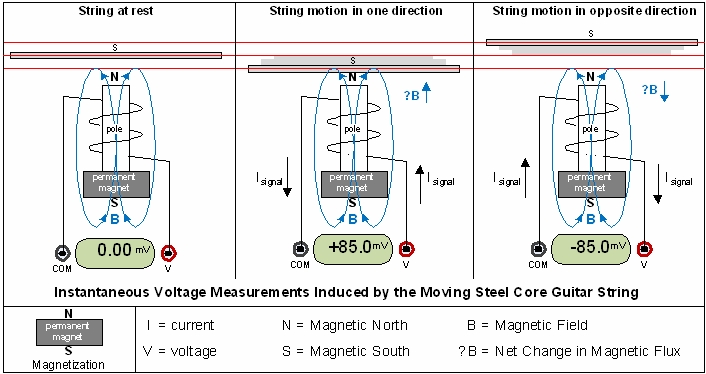

Electric guitars process the vibrations of the strings in a very different way to our ears. Guitars don't have a membrane that moves back and forth in response to the pressure variations in the air, like our eardums. Instead, they measure the vibrations in the string using magnets and electricity. To do this, they take advantage of Faraday's law of induction, using magnets and coils of wire placed directly below each of the strings. These magnets and coils might sound more familiar if we call them 'pickups', which you can easily see mounted into electric guitar bodies between the bridge and the neck. We'll look at the image below to explain the working principle, but bear in mind that pickups come in many flavours and so your pickups might not look like the ones in the illustration, but the basic idea is essentially the same for them all.

A permanent magnet is a material that is... permanently magnetic... This material can attract or repel metals with its 'magnetic force', and we can draw the field over which this force is acting with imaginary 'magnetic field lines'. Now if we sit a non-magnetic metal in this field, the magnetic force will cause that metal to magnetise, too. This piece of non-magnetic metal has now become a 'temporary magnet', meaning that it now also has a north and south pole as long as it is sat inside the magnetic field of the permanent magnet.

Now lets look at the below diagram. We have a non-magnetic metal (the pole) sat atop a permanent magnet. The pole has become a temporary magnet and so it's almost like we have one 'larger' magnet and so the magnetic field lines (the circular blue paths) that belong to the permanent magnet extend through the temporary magnet. If the pole wasn't there, the field lines would be much shorter, and would be symmetric about the permanent magnet rather than stretching all that way upward like in the diagram. In some pickups the pole will just be a permanent magnet by itself - like I said, different flavours.Things start to get a little messy here so just sit tight and we'll try our best.

So now we have a slightly bigger magnet, what next? Well you'll also see a wire spiraling up around the pole in the diagram. We call this a coil (of wire). In reality this wire actually spirals hundreds or thousands of times around the pole, rather than the two or three illustrated here. By placing the metallic guitar string in the vicinity of this magnetic field, the string also becomes magnetised! You can see this for yourself by holding a coin against your strings and feelng the attraction. So now as the string vibrates within this magnetic field, the shape and strengthe of the field changes and an alternating voltage is created in the coil of wire. This voltage is an electrical representation of the note you’ve just played. The voltage is a sinusoidal oscillation with a frequency equal to the frequency of the guitar string vibration, and an amplitude that relates to how ‘hard’ the string is vibrating [see appendix for detailed explanation – amplitude relates to speed (faraday/lenz) and if amplitude of vibration is higher, speed of nodes is higher at centre point].

Below is an illustration of the basic principle. As the string oscillates back and forth, so too does the voltage induced in the pickups.

A full understanding of this concept is not necessary. It has been presented here for completeness as we paint the picture of what causes

the input to our pedals

Image Credit: www.electricalfun.com