Important Concepts

Whilst this guide assumes a certain level of knowledge, there are some fundamental concepts that are really common and important in guitar effects pedals, and it's worth making sure we're all on the same page.

Expand a section to find out more.

Grounding

Correctly grounding your circuits is important. Incorrect grounding can create a shock hazard. Please check your circuits thoroughly to make sure the grounding is adequate.

You're plugged in and ready to go, but there's an annoying buzzing noise that stops when you touch a metal part on the guitar body. If your parents paid extra to install that spectrum analyser in their child as the kind doctor recommended, you'll recognise it as a \(50Hz\) or \(60Hz\) buzz. That's a grounding issue, my friend. What it means is that you have what's called a ground loop - when two parts of a circuit are supposed to be at the same electrical potential (\(0V\) in this case), but they're not. Often, audio equipment that is connected to the mains (an amplifier or effects pedal) will share the signal ground with the mains ground, and this means that the ground loop will actually pull the 'mains hum' into the signal, and amplify it (bzzzzz).

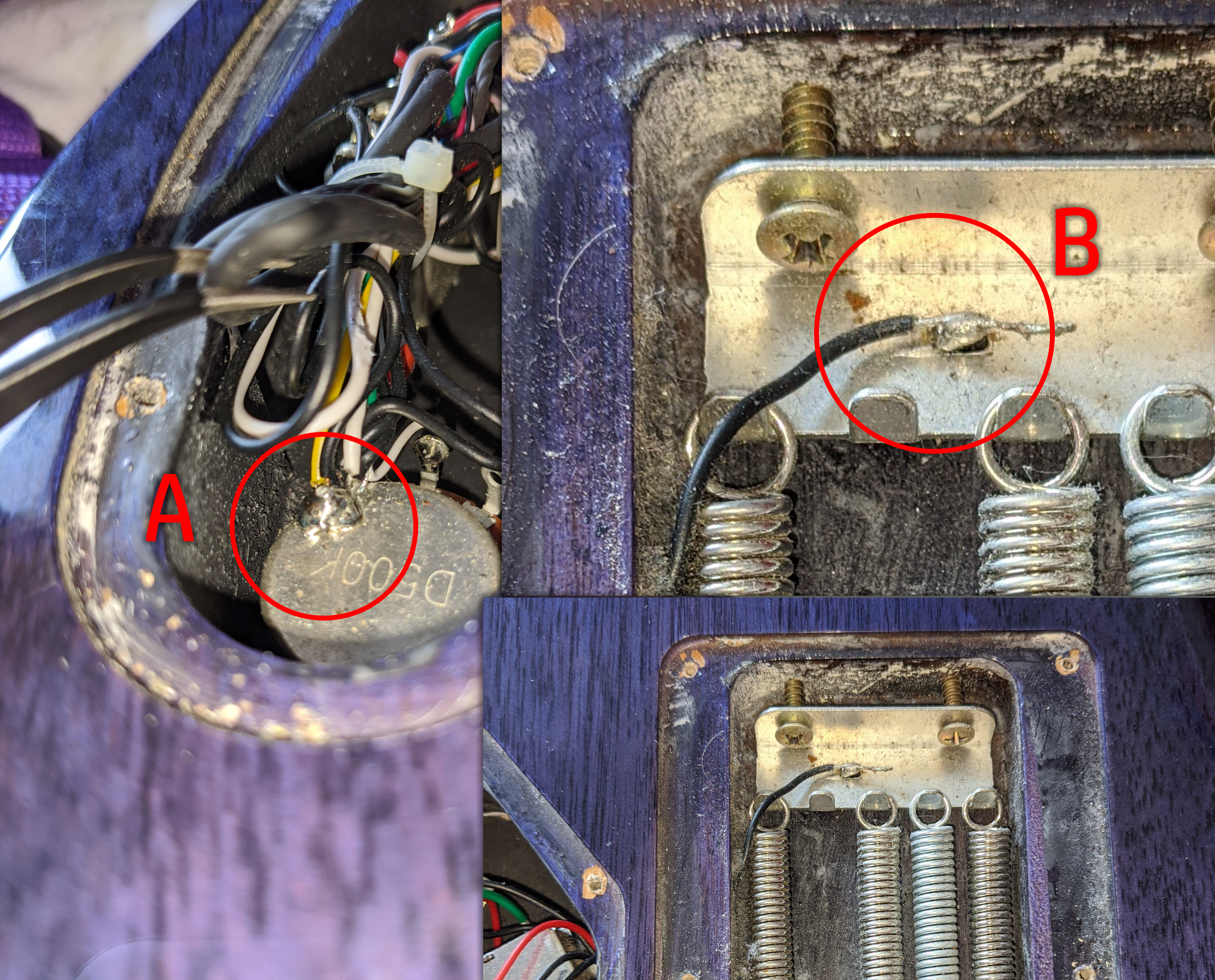

Grounding issues are pretty easy to avoid, however. If ground is just a point with zero electrical potential, we just need to find something conductive with (theoretically) zero electrical potential that will not easily charge to some non-zero potential once current starts flowing in the circuit. It turns out that really any conveniently placed decent-sized solid peices of metal will do the trick nicely. For example, let's take a look inside a guitar for a second:

In circle (\(A.\)), you'll see the blob of solder on the metallic body of the tone potentiometer, which is connecting several grounding wires from the circuit. In circle (\(B.\)), you can see a wire that has travelled from the electronics cavity and reappeared in the tremelo cavity, and is soldered directly onto the spring claw. Both of these methods are as discussed above - connect the circuit ground to large pieces of metal that will not easily increase their potential once current begins to flow.

In our circuits, potentiometers will be fairly common, and so we'll use those where possible. If we house our pedals in metal enclosures, we can connect to our chassis for grounding. If neither of these options are available, we should still be ok. We're still connected to the amplifier and the guitar grounds via the jack sockets and the jack plug Sleeve connections, and so as long as they've been grounded well, we should be alright... Wherever possible though, please properly ground your circuits!!

Active and Passive

This one is nice and simple. The circuits we'll look at will have both active and passive components.

A passive component is one that will only consume electrical power, and cannot produce any additional power of its own. Typically this just means that it does not have its own power supply (e.g. a resistor or an inductor).

An active component has a power supply of its own (see operational amplifiers for example). This means that it can draw power from this supply and 'inject' power into the circuit. The output of an op-amp can be much more powerful than it's input.

Impedance

Hopefully you have a decent grasp of resistance. Impedance is admittedly a little scarier (remember those imaginary numbers you thought you'd never need...). But for our purposes, the core takeaway is that impedance is the effective resistance of a component to alternating current. Remember how we said the vibration in the guitar string causes an alternating voltage level in your guitar circuitry? Perhaps it's obvious that this alternating voltage force pushes alternating current through the circuit, and so the impedance is a very important thing to understand and quantify.

Impedance is a combination of resistance and reactance. Resistors are our old friends! Of course, resistors are responsible for the resistance component of a circuit's impedance.

Reactance is just a little bit messier. Reactance is the 'effective resistance' that is offered by components like capacitors and inductors. The reason that reactance isn't so friendly is that reactance varies with frequency. Don't worry too much about the maths right now, but it might help your understanding if you look at how a capacitors reactance is defined: \[X_C = {1 \over 2 \times \pi \times f \times C}\]

A higher reactance, \(X\), is a higher effective resistance. So for any particular capacitor, (characterised by it's capacitance, \(C\)), the reactance gets higher as the frequency, \(f\), of the alternating current decreases.

If we have a \(10 \mu F\) capacitor (thats \({10 \over 1,000,000} F\)), then at the height of the human hearing range - \(20kHz\) - the reactance will be \(X_C \approx 0.8 \Omega \) - we could almost pretend the capacitor is just a bit of wire!

A perfect direct current will not vary over time - it has a frequency of \(f=0Hz\). If we put this into our reactance equation, we get a divide-by-zero error (whoops!), but we can say that the reactance is essentially infinite for a direct current, as if there is an open circuit where the capacitor is - a capacitor will 'block' direct currents.

Inductors are essentially the opposite in this sense. Their reactance increases as the frequency increases.

Voltage Dividers

A voltage divider is a combination of resistances in series. They're placed between some voltage level and ground, and they divide the voltage, so that at each junction, we have some fraction of the voltage that we have at the top of the divider.

Source and Load Impedance

Now that we have some understanding of impedance, we have to touch on a VERY IMPORTANT THING. As well as the impedance that exists all around our pedal circuitry, we must also consider what is happening at the output of our guitar, and at the input of out amplifier!!!

The reason for this is that the source (or the input - our guitar), and the load (or the output - the amplifier), each have some impedance at their connections. It's also true that any effects pedal will have a source and a load impedance, though conveniently they're usually designed to have high input impedance, and low output impedance, just like our amplifier and guitar respectively. We'll just focus on the guitar output as the source, and the amplifier input as the load.

Earlier, we had a quick discussion about pickups. A pickup is essentially some magnets and a coil of wire, and a coil of wire is essentially an inductor. And just to keep things interesting, the coil of wire also has a resistance and a capacitance... We also have our tone and volume circuits introducing some impedance too. All that this means is that we have to consider the effect that the internal circuitry has on our signal. The fun doesn't stop there, either - the cables we use will also present some impedance (primarily in the form of capacitance). These are all contributing factors to the source impedance, and so if we represent the induced voltage in the pickups as an AC signal source, our equivalent circuit might look something like this:

Bearing in mind all that we know about reactance, obviously the source impedance will vary with frequency. For any particular guitar, it will also vary with the selected pickups, volume and tone control positions, and the length of the cable. Further still, different pickups and different components in the volume and control circuits will have significant effects on the source impedance. It seems a bit silly to try and put a single number on this value, but we're going to do it anyway. For a guitar with passive, single-coil pickups, with tone and volume pots of size \(\approx 250k\Omega\) each at their 'maximum' position, we might expect a source impedance of \(\approx 10k\Omega\) in series with our AC signal. This is a value that we'll take as our assumed source impedance throughout our designs, but it is well worth remembering that this is highly variable.

With \(10k\Omega\) in series with our AC signal, we need to consider how we'll minimise the effect that this has on the strength of our signal. Now of course, we need to apply a load to our source. All this means is that we need some impedance between our signal and ground so that we aren't shorting the output of the source. Practically, this is simply done by introducing some input impedance between our signal line and ground. By loading our source, we actually create a voltage divider with the source and load impedances. Since the next element in the signal chain - whether effects pedal or amplifier - will essentally be measuring the signal across this input impedance, we need to make sure the majority of the voltage drop occurs over the input impedance, and a minimal voltage drop occurs over the source impdance.

DC Biasing

The AC voltage output from our guitar is centered around \(0V\). This means that it has zero DC bias (or DC offset). This is fine for some applications, but others require a DC bias to properly function. For example, operational amplifiers amplify a voltage input (according to whatever configuration you have built it in to). An op-amp is an active component, and so this amplification is achieved by pulling current from the connected DC supply. If we have a \(9V\) battery connected to the \(+/-\) supply rails of the op-amp, the output voltage can swing between \(0V\) (ground), and \(9V\). This means we will not see amplification of the negative half-cycle of the input, as it is outside of this range.

There are a couple of solutions to this problem. One is to use two power supplies, connecting the positive terminal of one to the negative terminal of the other. In the case of a \(9V\) battery, this creates a supply with \(18V\) between it's terminals. We can then ground the junction between the two batteries, so our op-amp positive supply is at \(+9V\), and the negative supply is at \(-9V\), allowing us to amplify the full cycle of our unbiased input.

We'll focus on a different solution, however, as it's easier than using two supplies. Since, with a single power supply, our output can only swing between \(0V\) and \(9V\), we can actually push our input up to the middle of this range. This way, a signal with peaks at \(+500mV\) and \(-500mV\) can be biased by \(4.5V\) (half of the \(9V\) supply), to become a signal with peaks at \(5V\) and \(4V\).

Current-limiting Resistors

Some components are especially sensitive.

Pull-down Resistors

There's a common phenomenon in guitar effects pedals - an audible pop noise when you un-bypass an effect by stomping it back into it's on state. This is something that's easily avoided by simply adding a resistor just on the inboard side of any switches.

As we saw in the impedance section, a capacitor 'blocks' direct current from flowing through it. This may be true for an ideal capacitor, but in the real world, things aren't so convenient. In reality, a capacitor will actually 'leak' a small amount of direct current through itself, from the higher potential port to the lower. This leakage current is essentially the cause of this switching pop.

Let's say we have a coupling capacitor in series with our input in order to add a DC bias to the AC signal. If we bypass the effect, we are leaving one leg of the capacitor 'floating' (disconnected), but the other leg is still connected to our biasing voltage. Initially, the floating leg will be at whatever potential the input was at when we disconnected (somewhere around \(0V\)). This potential difference forces the leakage current through the capacitor, gradually increasing the potential of the floating leg, until both legs are at the same potential (the biasing voltage). Our AC signal has a DC offset of \(0V\), and so when we switch the effect back on, there is a sudden rush of current through the load as the biasing voltage comes into contact with a much lower voltage, which is then amplified etc. and we hear that not-so-attractive pop.

The solution to this is a pull-down resistor.

Coupling Capacitors

So we know that capacitors 'block' direct current. This is a really useful property when it comes to designing guitar effects pedals. Our AC input signal is centered around \(0V\), meaning it has no DC offset. For some applications, however, we need to add a DC offset to our signal so that it's instead centered around \(4.5V\), for example.

The biasing voltage can be easily achieved by using a voltage divider to give us some fraction of a DC supply (like a \(9V\) battery).

Smoothing Capacitors

The real world isn't quite as nice as the idealised one we like to work in. Whilst an ideal DC voltage source should produce an unchanging voltage across it's terminals, the real-world isn't so kind. An actual DC voltage source might vary slightly over time (more-so a wall wart than a battery, but it really should be considered in any case).

Frequency Filters

Remember when we represented the frequency content of a note using a frequency spectrum? That representation might be quite useful here too. If we want to modify the frequency content of our signal, we can apply a frequency filter. You should be familiar with frequency filters, because this is what the tone potentiometer on your guitar is doing.